Build Distributed Systems: Enabling Resilience

Learn how we can enable Resilience in our in-memory caches with the help of Write-Ahead Logging using Protocol Buffers and tune-able Fsync strategies.

In-memory caches are the backbone of high-performance systems, critical for their speed. But a simple application restart or a server crash wipes the entire dataset, leading to cold starts, performance degradation, and potential data losses.

This article tries to evolve our Compact Go cache from an ephemeral toy-cache into a durable, crash-resilient data store. We'll explore the design choices, trade-offs, and implementation details of adding a persistence layer using a Write-Ahead Log (WAL), a technique used by relational databases like MYSQL/PostgreSQL for guaranteeing durability.

Core Concept: The Write-Ahead Log

The principle of a WAL is simple yet powerful: before any change is made to the in-memory data, the intent of that change must first be recorded in an append-only log on disk.

Append Only: When a SET or DELETE operation occurs, we don't overwrite data on disk. We simply append a new entry to the end of our log file, such as [SET, key="user:1", value="alice"].

Replay on Startup: If the application crashes and restarts, the cache is initially empty. To restore its state, it simply reads the WAL file from beginning to end, replaying each operation in order. After replaying the entire log, the in-memory state is restored to where it was just before the crash.

The append-only design of WAL is incredibly fast, as it avoids slow, random disk I/O in favour of sequential writes.

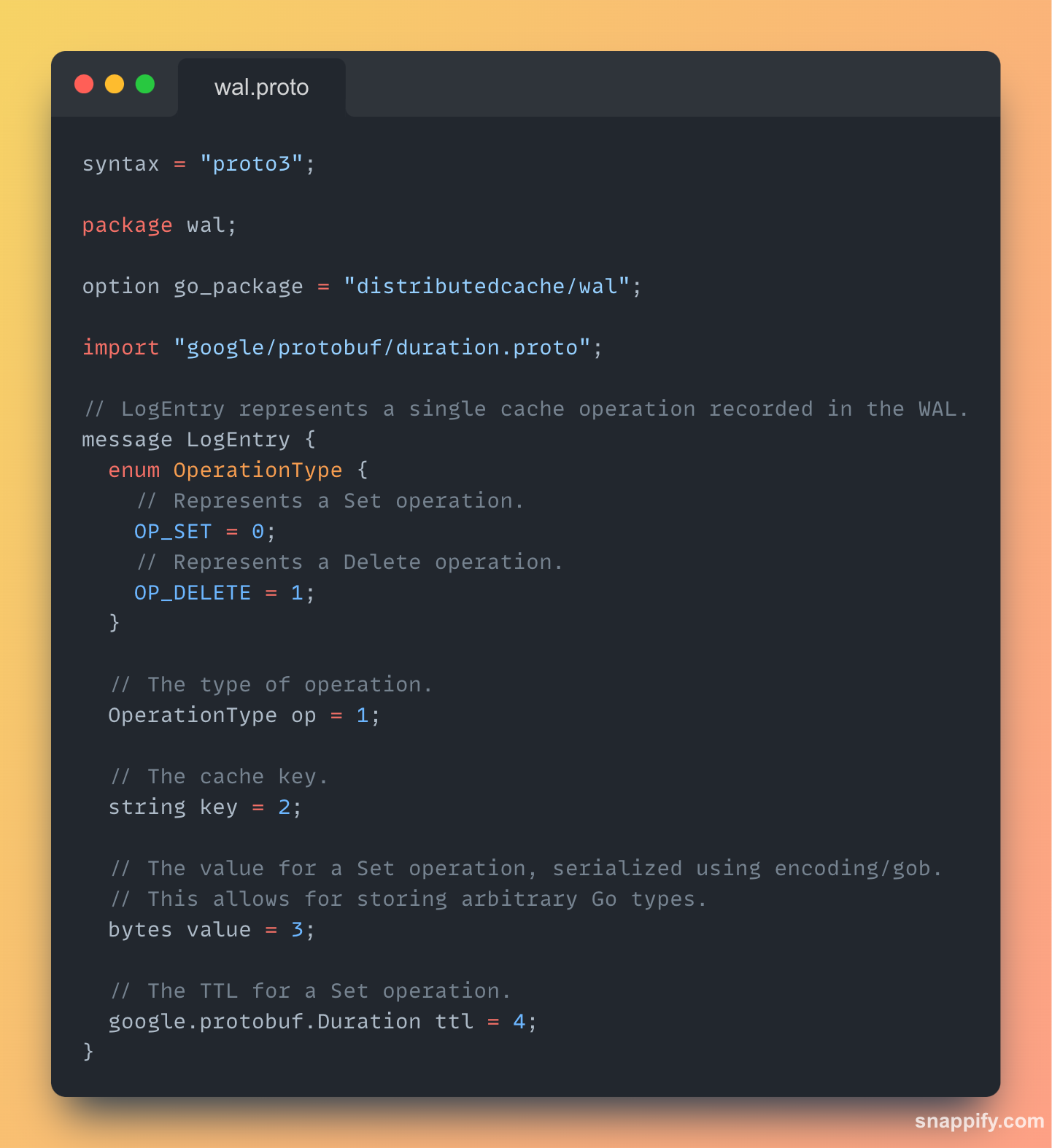

Design Choice 1: The Log Format — Why Protocol Buffers?

The first critical decision is the format of our log entries on disk.

Option 1: We could have leveraged a custom binary format combined with Go's native gob package.

While simple, this approach has some drawbacks:

Brittleness: A custom format is hard to change. Adding a new field in the future would require writing complex, manual version-handling logic.

Go-Specific: The gob format is a black box to any non-Go application, making debugging, analysis, or ecosystem integration nearly impossible.

Option 2(Preferred): We opted for a more robust solution: Protocol Buffers (Protobuf).

The advantages of Protobuf are:

Performance: Protobuf is an order of magnitude faster and more compact than gob or JSON.

Schema Evolution: We can add new fields to our LogEntry message, and Protobuf's backward-compatibility rules ensure that older versions of our software can still read the log without breaking. This provides immense long-term flexibility.

Interoperability: The .proto file is a universal contract. The WAL can now be easily understood by tools written in Python, Java, Rust, or any other language.

We still use GOB somewhere. Find out where and think about the WHY!

Design Choice 2: The On-Disk Record — Preventing Corruption

Simply writing the Protobuf messages back-to-back on disk is not enough. A crash could leave a partially written message at the end of the file.

To solve this and protect against disk corruption, we implemented a length-prefixed, checksummed record format for every entry:

[Length (variable)] -> [Checksum (4 bytes)] -> [Protobuf Data]

Length Prefix: Before writing the Protobuf data, we write its length as a variable-length integer (uvarint). When replaying the log, the reader first reads this length, so it knows exactly how many bytes to expect for the upcoming record.

Checksum: After calculating the Protobuf data, we compute a CRC32 checksum of it and write that checksum to the log.

During replay, we read the data, re-compute the checksum, and verify that it matches the one stored on disk. If it doesn't, we know the record is corrupt and can stop the replay to prevent loading bad data.

This record structure makes our WAL robust against the realities of system crashes and disk failures.

Design Choice 3: Defining Endianness

In our record format, [length][checksum][data], the checksum is a raw 4-byte number. Endianness is simply the rule that defines the order of those 4 bytes in the file.

Why It's Critical for Our WAL:

Portability: We must ensure a WAL file created on a server with an Intel CPU can be read correctly on a server with an ARM CPU. These architectures have different internal byte orders. By choosing a standard, we make the file portable.

Data Integrity: If we didn't enforce a single, consistent byte order, the 4-byte checksum would be read as a completely different number on a different type of machine, causing false corruption errors and making the WAL unusable.

Our Design Choice:

We chose BigEndian because it's the universal standard for portable data formats, often called "network byte order." This is a conventional and safe choice that guarantees the file can be read correctly on any system.

Design Choice 4: Tuning Durability

This is the most critical and nuanced part of any persistence engine. When our application writes data, it's not immediately saved to the physical disk.

It's passed to the operating system's in-memory page cache for performance. If the server loses power before the OS flushes this cache to disk, the data is lost.

The fsync system call is our control knob. It allows us to order the OS: "Flush all buffered data for this file to the physical disk *now*, and do not return until you are done."

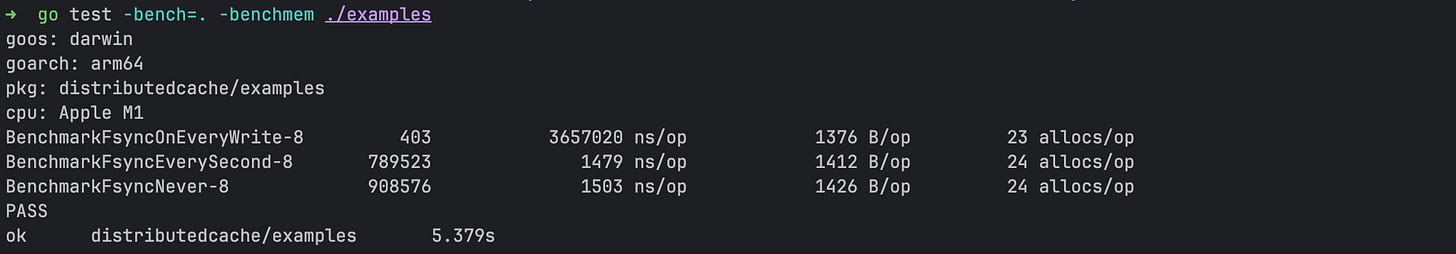

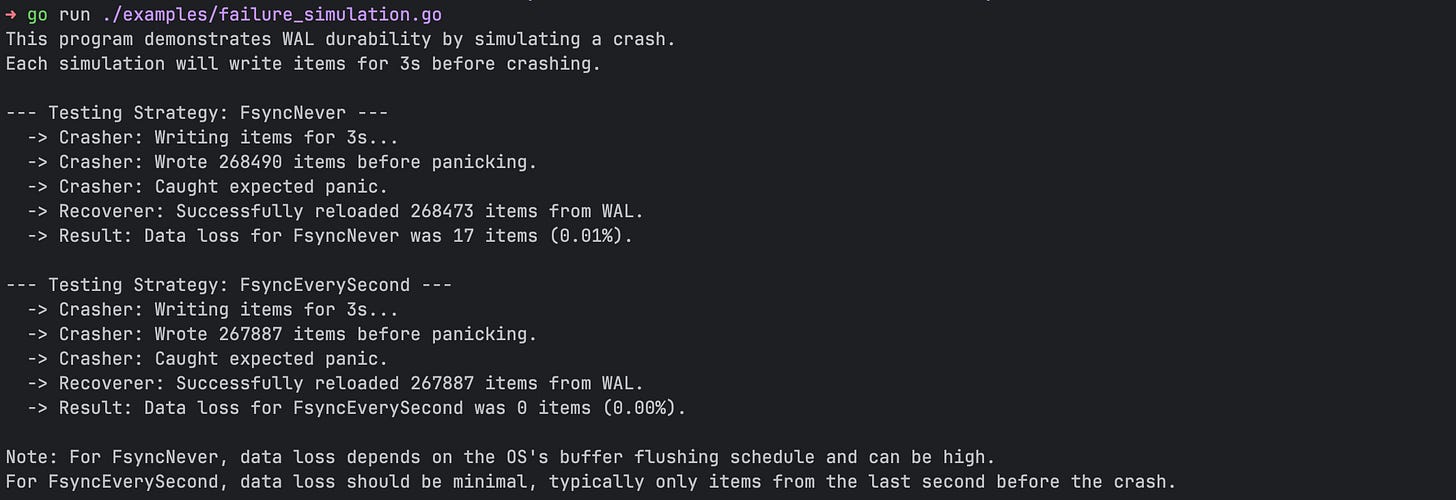

Calling fsync is a heavy operation that guarantees durability at the cost of performance. We implemented three strategies, mirroring Redis's AOF, to let the user choose their own trade-off:

FsyncOnEveryWrite: After every single Append operation to the WAL, we call fsync.

Durability: Every successful write is guaranteed to be on disk.

Performance: Extremely slow. Our benchmarks show it's orders of magnitude slower than other options, as every write must wait for a slow disk operation.

FsyncNever: We never explicitly call fsync and rely entirely on the OS to flush the buffer when it chooses.

Durability: Very low. A crash could result in the loss of several seconds (or more) of data.

Performance: Blazing fast. All writes happen at memory speed.

FsyncEverySecond(Default): A background goroutine calls fsync once per second.

Durability: Excellent. In a crash, you risk losing, at most, the last second's worth of writes.

Performance: Almost identical to FsyncNever. Writes are still written to the fast memory buffer, and the slow fsync call happens periodically and concurrently in the background.

Our failure simulations confirmed this behaviour perfectly.

FsyncEverySecond provides nearly the full performance of FsyncNever with a vastly superior durability guarantee, making it the ideal default for most applications.

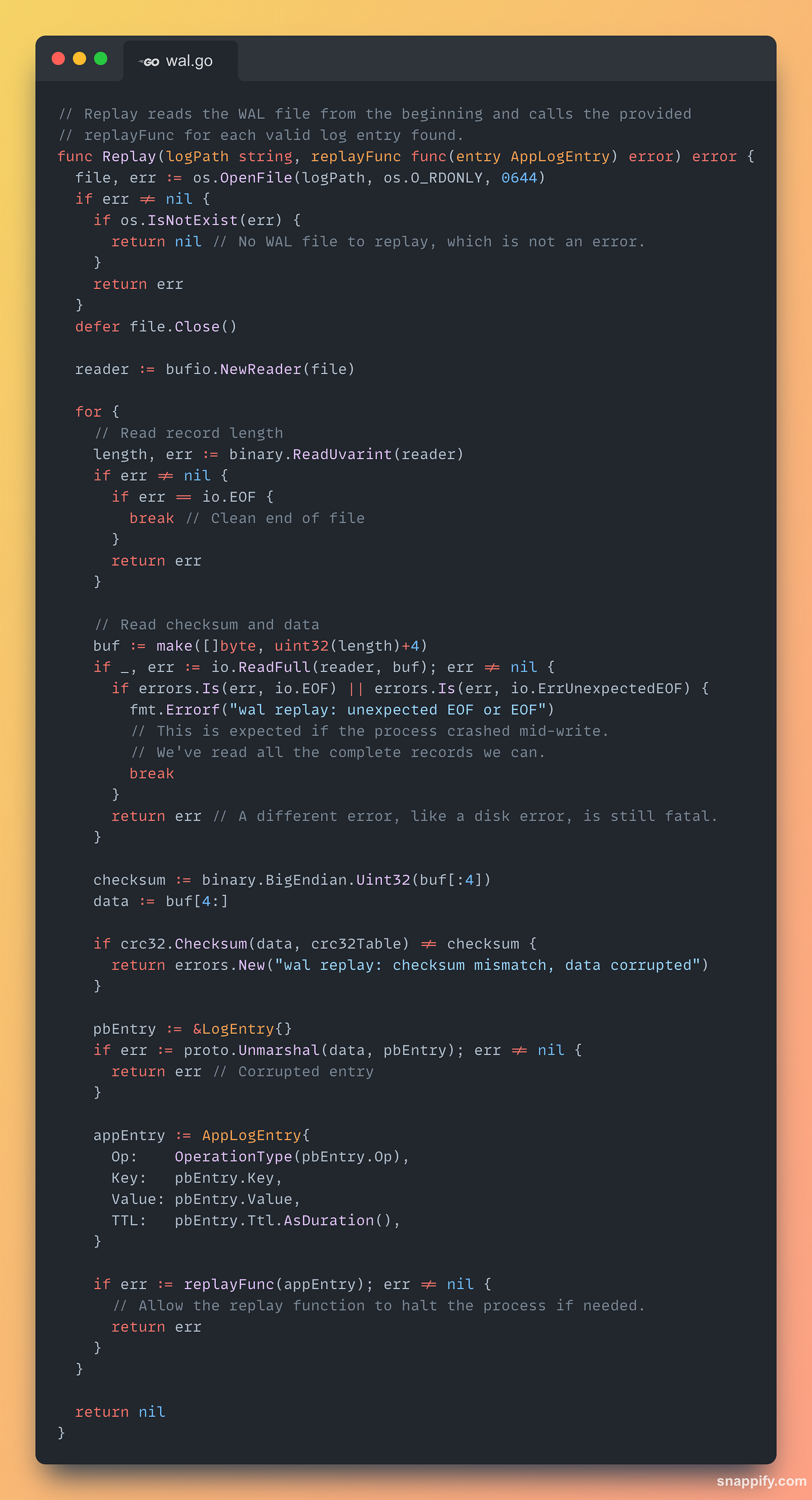

Implementation Details: WAL Replay

The Replay function was designed to be resilient. A crash will almost certainly leave a partial, torn record at the end of the WAL.

Our replay logic correctly handles this by treating an unexpected EOF error not as a failure, but as a clean signal that it has reached the end of the last complete record.

For each complete record, we also see if the checksum of that entry matches the already generated value to validate corruption.

👉 Connect with me here: Pratik Pandey on LinkedIn

👉 GitHub - https://github.com/pratikpandey21/distributedcache

Conclusion

By implementing a Write-Ahead Log, we transformed our cache from a simple, volatile tool into a durable data store. The design choices—using Protocol Buffers for a flexible schema, a checksummed record format for data integrity, and tunable `fsync` strategies for balancing performance and durability—provide the foundation for a production-ready cache.

There are some other design choices in our implementation. I’d love it if you can identify those and start a discussion on those choices!

Note on Production Readiness: Log Compaction

The one critical feature our current WAL implementation has deferred is log compaction (also known as log rotation or rewriting). In the current implementation, our WAL file will grow forever. This is unsustainable for two reasons:

Wasted Space: If you SET the same key 1,000 times, there will be 1,000 entries in the log, wasting space.

Slow Recovery: On startup, we have to replay the entire log. A 50 GB log file could take minutes to replay, leading to unacceptable downtime.

The solution to the above problem is Log Compaction. This is something I’ve not implemented yet, and might get to it later.