Build Distributed Systems: Optimising Memory Usage of our Caches

We use Redis as an inspiration, to implement memory efficiencies in our cache and reduce our memory usage by 45%!

In our last post, we dived into different Eviction algorithms and understood the different cases in which the different types of eviction algorithms will be useful.

However, at the end of the post, we questioned the memory usage because of the auxiliary data structures to manage eviction and questioned if it’s feasible to use them for an in-memory application like a Cache. In this post, we try to optimise our cache in terms of it’s memory usage, take inspiration from Redis and implement optimisations that allow us to have nearly 45% memory efficiency.

Problem with Optimised Cache Implementation

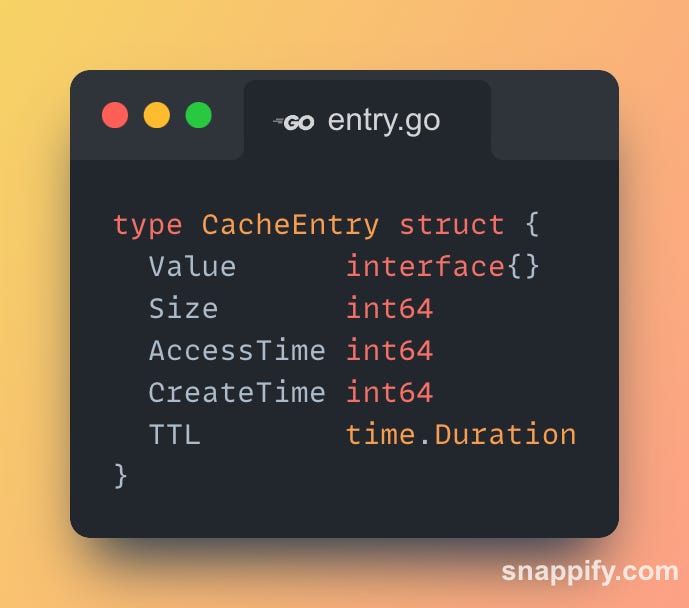

Our "Optimised" cache, while performant, consumed a lot of additional memory to gain its performance. Its entry structure and eviction mechanisms carry significant memory baggage.

In addition to the cache entry, we had eviction metadata per key as well :

For LRU: A map entry + a linked-list node with 2 pointers (16 bytes).

For LFU: A map entry + a heap item with frequency, etc. (24+ bytes).

For a cache with a million entries, this structure consumes vast amounts of memory before even storing the actual values. The separate, pointer-heavy structures required for eviction policies like LRU (linked lists) and LFU (heaps) only increase the problem, easily adding another 16-24 bytes of overhead per entry.

Furthermore, creating a new entry object on every Set operation puts constant pressure on the garbage collector.

Solution: Compact Cache

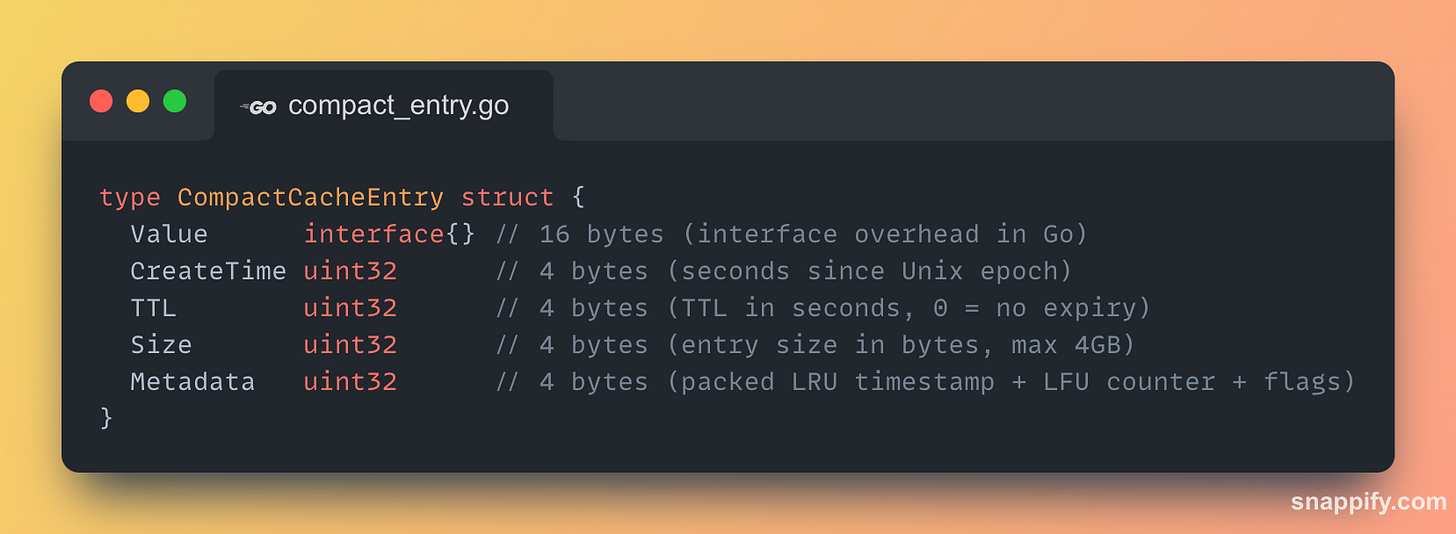

Our compact cache implementation takes a fundamentally different, Redis-inspired approach that prioritises memory density above all else.

This structure immediately saves 12 bytes per entry on core fields alone.

But the real advantage of this approach lies in how it leverages the Metadata field and eliminates external tracking structures entirely for evictions.

Key Memory Optimisations

1. Reduced Integer Sizes

int64 → uint32 for timestamps is safe until the year 2106 and is perfect for cache entry lifetimes.

time.Duration (an int64) → uint32 seconds is more than sufficient for cache TTLs (up to 136 years).

2. Packed Metadata: The "Eviction" Field

The single uint32 Metadata field replaces the need for external linked lists or heaps by storing eviction data directly within the entry.

For LRU: It stores the last access time as a uint32 timestamp.

For LFU: It stores an 8-bit probabilistic "Morris" counter, packing frequency information into a tiny space.

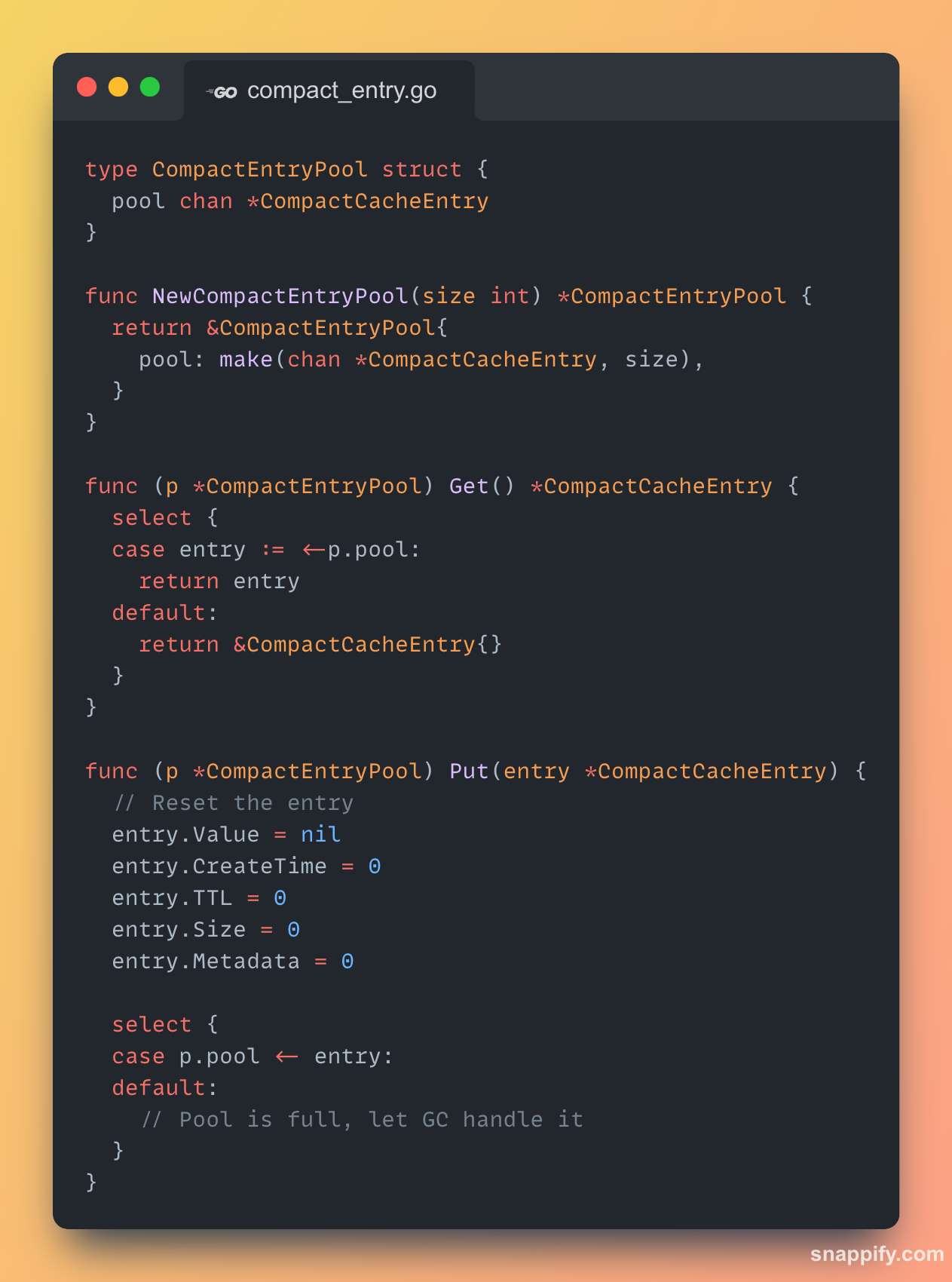

3. Object Pooling with `sync.Pool`

The optimised cache allocates a new CacheEntry on every Set. The compact cache uses a sync.Pool to recycle CompactCacheEntry objects, drastically reducing allocations and GC pressure.

Eviction Policy Optimisations

LRU Optimisations: Sampling, Not Pointers

Our OptimizedLRU implementation, required a doubly-linked list to maintain a perfect ordering of items. This adds two 8-byte pointers to every single entry, a massive memory cost.

The CompactLRU eliminates the linked list entirely. To find a victim, it employs sampling:

It selects a small, random sample of keys from the cache (e.g., 16 keys).

It places these candidates into a small, temporary "eviction pool."

It inspects the Metadata (LRU timestamp) of only those 16 candidates and evicts the oldest one from the sample.

This approximation is incredibly effective. With a sample size of just 16, it achieves ~98% the accuracy of a true LRU implementation while saving 16 bytes of pointer overhead per entry.

LFU Optimisations: Morris Counters

Our OptimizedLFU uses a standard min-heap, which requires O(log n) time for updates and significant memory for heap items.

The CompactLFU uses a probabilistic algorithm called Morris counter, which allows it to track frequencies

Understanding Morris Counter

A simple frequency++ counter is problematic for LFU.

It can grow infinitely, requiring a large integer.

It suffers from "cache poisoning," where an item accessed frequently in the past pollutes the cache and never gets evicted.

The Morris counter is a probabilistic algorithm that solves both problems. Instead of incrementing on every access, it increments based on a probability that decreases as the counter's value grows.

The core mechanic is:

if rand() < 1 / (2^counter) { counter++ }When counter is low (e.g., 1), the probability of an increment is high (1/2). It tracks initial accesses closely.

When counter is high (e.g., 10), the probability is very low (1/1024). It takes many more accesses to register an increment.

This gives the counter a logarithmic behaviour. It tracks the order of magnitude of accesses, not the exact count. This allows us to store a massive frequency range within a tiny 8-bit integer (0-255).

In addition, with the decay mechanism (periodically halving all counters), the cache can adapt to changing access patterns, allowing previously unpopular items to become "hot" and old, unused items to be evicted.

How LFU Eviction Actually Happens

The Morris counter is only for tracking frequency. So, what's next? How is a victim chosen for eviction?

A naive approach would be to scan the entire cache to find the entry with the lowest counter, but this would be an O(N) operation and would destroy performance.

The CompactLFU implementation avoids this by reusing the exact same sampling strategy as the `CompactLRU`.

Here is the full LFU eviction process:

Sampling: When the cache is full and needs to make space, it does not scan the store. Instead, it selects a small, random sample of keys (e.g., 16) and places them in a temporary eviction pool.

Comparison: It then inspects the Morris counters (from the Metadata field) of only those sampled keys.

Victim Selection: The key from the sample with the lowest frequency counter is chosen as the victim and is evicted.

Redis does not use a timer to scan and decay keys.

Instead, when a key is accessed, Redis checks the last time it was decayed.

It calculates how much time has passed and applies the appropriate amount of decay at that moment, just before incrementing the counter.

Trade-offs

Optimised LRU: Offers perfect O(1) operations for both access and eviction selection. This is its biggest advantage, but it comes at the cost of a pointer-heavy linked list that consumes significant memory.

Compact LRU: Achieves O(1) on access and amortised O(1) on eviction (since sampling a small, constant number of keys is independent of the total cache size). It trades perfect accuracy for zero memory overhead.

Optimised LFU: Suffers from O(log N) complexity on every access, as the heap must be rebalanced. This can become a bottleneck in write-heavy caches.

Compact LFU: It provides O(1) access time and amortised O(1) eviction time with zero extra memory overhead. It sacrifices perfect frequency counting for a probabilistic model that is highly effective in practice and vastly more scalable.

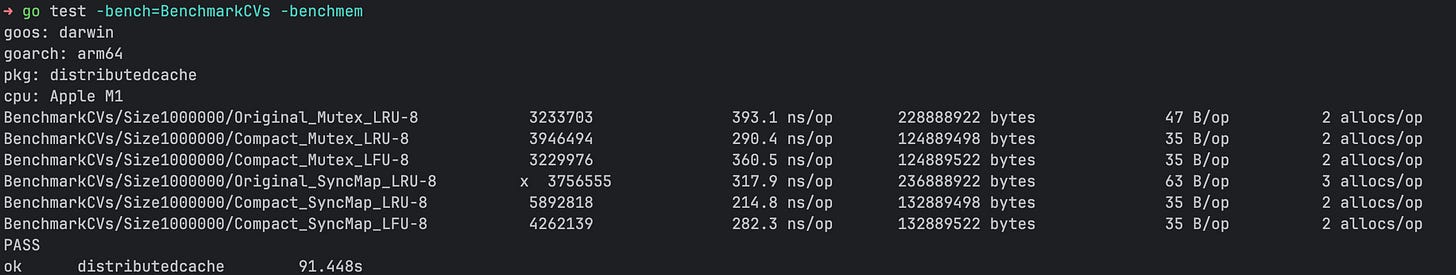

Performance Benchmarks

Our benchmarks show the dramatic impact of these optimisations:

We’re looking at almost 45% memory efficiency gain for the Compact implementations compared to the Optimised implementation.

The savings come from the combination of smaller entry fields, the complete elimination of eviction data structures, and reduced GC pressure from object pooling.

Key Difference in Compact Setup: Mutex vs. Sync.Map

We implemented both mutex and sync.Map variants of our cache. The sync.Map version of the compact cache highlights a key challenge:

Eviction sampling requires a list of keys, which sync.Map does not efficiently provide.

The solution was to maintain a separate, mutex-protected map[string]*CompactCacheEntry (storeRef)purely for the purpose of sampling, a trade-off that adds memory overhead but enables highly concurrent reads.

👉 Connect with me here: Pratik Pandey on LinkedIn

👉 GitHub - https://github.com/pratikpandey21/distributedcache

Conclusion

The compact cache implementation proves that enormous memory optimizations are achievable by rethinking core design principles. By trading absolute precision for clever, Redis inspired approximations, we achieved a 45% memory reduction while maintaining comparable or even better algorithmic complexity.